In order to complete her joint master’s programme in Urban Studies, Lisbeth Huber would have traveled to Tanzania. Due to Covid-19 she had to find methods to collect relevant data even from a distance.

I chose to study Dar es Salaam, the largest city of Tanzania, because of various coincidental events during my search for a master thesis topic. I went to a presentation in Copenhagen, during the C40 summit and learnt about innovative green infrastructure projects in Dar es Salaam. The next day, I joined a film screening on informal housing and resettlement programmes in Addis Ababa Stina. Both encouraged me to follow my interest in learning more about Dar.

Urban issues new to Europe

Later I argued in my thesis that I wanted to study a country outside the European Union to extend my knowledge on urban issues new to Europe but common in other countries with little resources to tackle them. The colonizing past of Europe also influenced the urban development of former colonial cities and gave me a more comparable case. Similarly, to Europe, Tanzanian land is primarily private but has to deal with rapid growth which poses serious threats on well-being and needs of adaptation.

Additionally, Dar has one of the highest informal settlements within its city of 75 per cent. Because the Dar has received academic attention in other urban study areas, adding knowledge on home making practices further nuances understanding.

How to deal with a global pandemic in ethnographic research?

Eventually, I established contacts with local researchers, academics and informal settlers to generate data and received the KWA scholarship from the University of Vienna. Initially, I wanted to visit Dar’s neighbourhoods by travelling to Tanzania. However, due to the global pandemic data collection methods applicable from afar had to be utilized. Hence, my research uses three forms of in-depth qualitative data collection methods, namely photo-elicitation, semi-structured interviews and picture analysis on social media.

First, individuals living within informal settlements had to take pictures of places in their neighbourhood that make them feel at home. Second, I interviewed the informants to understand what those pictures present. The interviews are semi-structured in order to guide the general theme but also to allow interviewees to determine the speed and extensiveness. Third, the potential criticism of bias from informants who know they are being studied (especially so from a researcher of the Global North) is compensated via an inventory of Instagram posts.

How did the ethnographic research process develop?

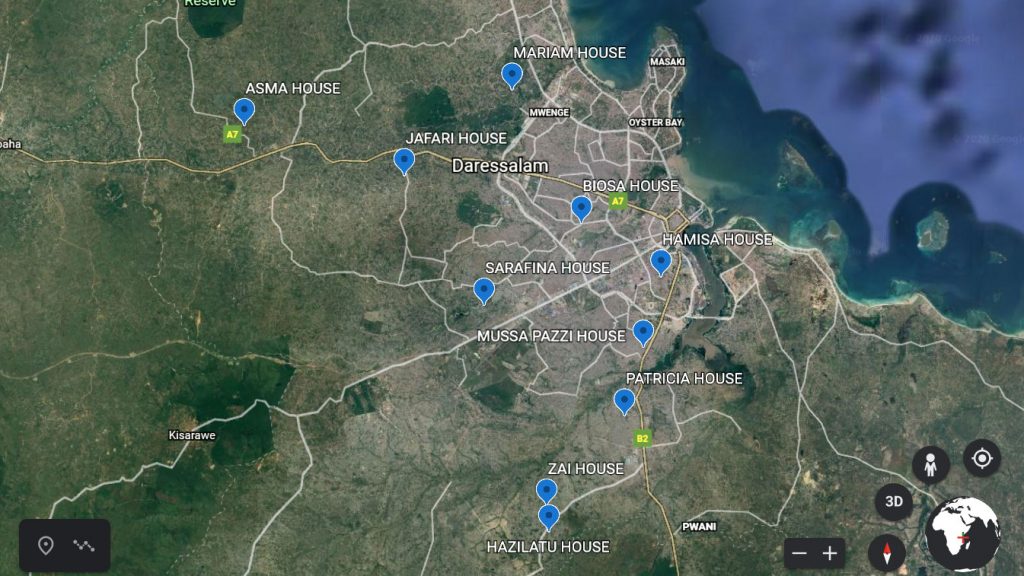

The main analysis uses data collected online and via skype from May to August 2020. During this time, I conducted 10 semi-structured interviews with residents of various informal districts. An initial assessment of Dar es Salaams current informal settlements, their distribution and location, as well as the study of existing research in the eight months prior to the data collection informed this research´s theoretical framework. The availability and successful recruitment of informants determined the location of the informal areas covered. I rejected Instagram images, which displayed advertisements and pictures portraying inside places of residents. Only places outside peoples´ homes such as streets, markets and symbols were used. The aim was, to understand their presentation of home on a digital platform. Data collection for the inventory took place within a 2-month period from the beginning of June 2020 to the end of August 2020.

Generate in-depth data

The limited time and aim to generate in-depth data lead to only 10 informants. Of those, all were available for interviews and sent back the requested pictures within four months. By the end of the social media inventory period, data had been collected from 32 different Instagram accounts resulting in 35 pictures to analyse. These are generated by searching for pre-defined hashtags using synonyms in Swahili for the word “home”, such as nyumbani. The content of the pictures is then analysed by looking for the location. Whether it was taken in Dar es Salaam and there within an informal settlement. Those additional insights can be related to existing knowledge in future research to form an encompassing analysis of Dar.

Asking participants to present their places of home in pictures gives them the opportunity to be creative and engage unselfconsciously in the task. Haywood (1990) suggests that images help to show meaningful locations and help analyse temporary settings and similarities in detail. In photo elicitation the images are used as starting point for verbal discussions to reveal underlying meanings and layers. Deep feelings, memories and ideas are evoked and contribute to novel understandings of home making.

After receiving the pictures taken by informants, I interviewed them via Zoom, WhatsApp and skype, depending on which provider worked best at the time. The average time of the interviews were 70 minutes, during which the research assistant translated my questions into Swahili and the answers into English. After a little introduction, participants were asked to describe the content of each photo one by one, particularly how it represented home and why. In my research, I aimed to contribute to the current academic discussion by presenting the dimensions of home-making within informal settlements, the new normal in today´s globalized world.

The following images present an overview of the material they sent to me.

It was a great experience to work with the Institute for Human Settlement Studies at Ardhi University. I am especially grateful for the guidance of Dr. Tatu Mtwangi-Limbumba and Emmanual Njavike for assisting me with my research as a reliable and resourceful translator. I hope to be able to visit Tanzania at a different point in time, outside a global pandemic and meet the wonderful people I had the chance to interview. Asante Sana.

Further readings

Research at the National History Museum of Los Angeles

Mit Stipendium auf Kriegsfolgenforschung (in German)